I was very impressed by several statements that James Curnow made during his clinic with the students from the College of New Jersey Wind Ensemble at our NJMEA conference this past February [1997]. I think that his comments about score study were truly profound, and triggered my own thinking about it–and hence this article. To summarize: he said that most school band conductors chose their career partly because of the aesthetic joy that one receives when being involved with music. But because of the stresses of the job (telephone calls, fund raising, and other administrative demands), directors often do not have time to approach music from a musical orientation. This causes some to become frustrated, and even leave the profession because they experience few satisfactory musical rewards; music is not really part of their lives. In recent correspondence Curnow stated: “the concept regarding an aesthetic experience for conductors through score study and analysis struck me sometime ago, and I have promoting the idea for the last few years. We all go into the business because we want to make music, however most of the time our truly aesthetic experiences are few and far between because of all the non-musical things we are required to do.”

The genius of his idea is that while we can gain immeasurable aesthetic personal benefits from score study, we will also be better prepared to teach and conduct the music in question. Rarely, do we find such double-win situation.

Priorities

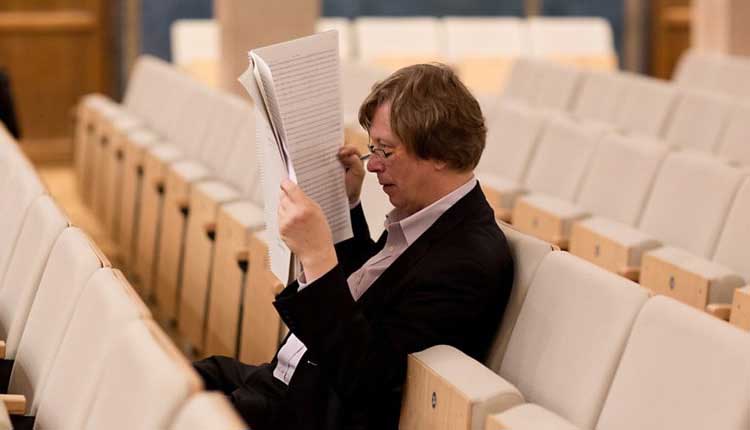

Time is definitely a 4-letter word–there is never enough. Given the pressures of being a band director/conductor, it is very easy to become overwhelmed by administrative requirements; score study can easily be postponed in favor of seemingly more pressing problems. This is certainly the case in my own life where it seems that there is a constant series of crises crossing my desk. The solution that I have found is to schedule an appointment for myself to study scores; phones are turned off and no other appointments are scheduled. I have established this time as a priority for me to analyze scores and to prepare for rehearsals. And I do this without fail. I always find new insights in the music, even after multiple performances; it is an endless, but rewarding process.

I constantly tell my students that there is a considerable and profound difference between playing and practicing. Even the words imply a difference. Playing is recreational and practicing is work; play is fun and practice is rewarding, but often not fun. There can be a parallel in score study. Serious analysis may not be fun, and may indeed be a great deal of work. Personally, I many times find score study to be difficult and frustrating, and it is sometimes tempting to do something else instead. However, it can be incredibly rewarding when you begin to discover some previously undiscovered insight, not unlike solving a difficult puzzle.

Another word comparison is between director and conductor. A director is an administrator; a conductor is a musician leading an ensemble. As band leaders, we need to wear both hats. When we wear our director’s hat, we perform the many administrative tasks that are a part of our job. But we are also conductors, fulfilling the role of musical leadership. In order to do this, we must do what professional conductors do: study scores.

Some scores require only a minimum amount of study. Certainly, a straight forward grade 2 work requires less analysis than a complex, modern, grade 5 or 6 composition. However, there are still questions to be answered in even the less complex compositions. I still am amazed over the simple yet clever construction of Air for Band by Frank Erickson. When I recently looked at a score that my wife (an elementary band director) was preparing, I was amazed to see how clever some of the compositional techniques were in that relatively simple grade 2 work. It may not take a great amount of time, but personal study will reveal greater insight no matter the level of difficulty.

Score Study Approaches

Mr. Curnow’s idea suggests a somewhat different approach to score study than that which might have been suggested in some conducting classes. The classic method would be to study each instrument’s part to make sure that actual performance is accurate and correct, and this is certainly an important task. His is a more analytic method where, in addition to the above approach, the conductor studies the work theoretically, looking at such elements as harmony, structure, and form, using those tools learned in theory and analysis classes. I find that the study of form is the most important of those areas. By looking at phrase length, use and development of themes and motives, and large structure, the conductor can gain considerable insight into developing his/her performance interpretation.

There are many different analytical approaches depending on different musical styles particularly with advanced harmony and melody. While discussion of the various strategies (i.e., set theory) is beyond the scope of this brief article, it is important for the conductor to re-visit the theory books if her/his skills are a bit rusty. This kind of growth can be re-vitalizing, and in itself rewarding.

Perhaps a first step to score study is to research the background surrounding the work in question and its composer. Often magazines and journals present articles on selected compositions; The Instrumentalist regularly features analyses of band compositions. Research publications include The Journal of Band Research and the CBDNA Journal. There are a number of books that are excellent resources: Best Music for Young Band (music graded 1-3) and Best Music for High School Band (music graded 4-5) are excellent. There are even resources available on the WWW: www.ed.uiuc.edu/students/heidel/major_project.html is a good source for an analysis bibliography. Many publishers are developing home pages that outline some composers and their works. Another source of information is program notes from performances and recordings. Of course, clinics like Mr. Curnow’s are also most valuable. There might be no better way to learn about a composition than to hear a composer speak about his or her own music.

There is some controversy over listening to recordings as part of one’s score study. I believe that this can be a good approach as long as one realizes that certain problems can arise. The obvious one is that the conductor’s interpretation can become entirely based on the recording. However the recording can be an invaluable reference both when analyzing form and other theoretical elements as well as serving as a departure point for evaluating interpretation. At the most recent Mid-West Band and Orchestra Clinic in Chicago [1996], Eugene Corporan suggested using multiple recordings to hear different interpretations as well as to guard against the problem of not being original in interpreting the score. For a conductor to ignore recordings seems to be an archaic notion. Recordings can be a valuable resource for learning about the sound heritage of a certain work, and can help in the theoretical analysis.

Final Thoughts

I fully realize that score study will not solve the many problems that we all face as band directors/conductors, and that the notion might seem to be overly idealistic to some. No matter how musical we are, budgets will still be reduced, and score study will not solve block scheduling. With this said, I encourage you to make a commitment to find the time to study scores. Hopefully, you will find aesthetic reward in the analysis process. Both you as a musician and your students will be rewarded.