Last week, the staff of the Wyandotte-Roosevelt High School Band and I had a great conference call meeting in which we discussed each of our agendas for the show and then melded them into one cohesive plan. As a drill designer, it is always good to get input from as many different sources as possible and Mark did an excellent job of gathering together not only his creative staff but his marching techs as well.

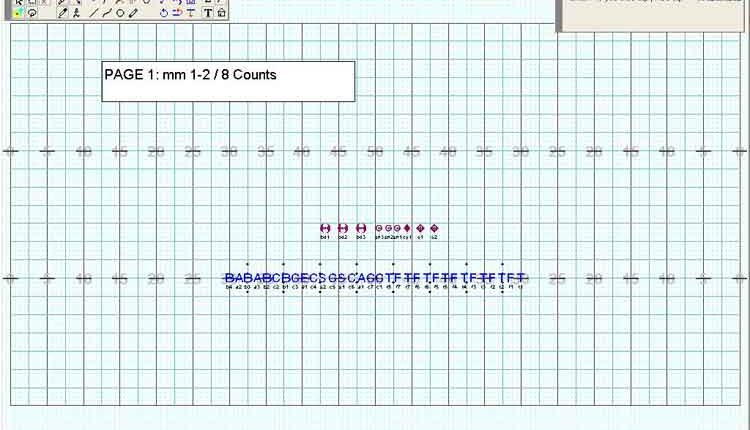

We began our meeting by going through the count sheet (see the previous article) and calibrating our thoughts as to phrasing, harmonic densities, and velocities. It’s always good to make sure that you are interpreting the phrasing in the same manner as the music staff to avoid any awkward moments in the show’s flow.

After our initial conversation with regard to phrasing, we dove into brainstorming. The most asked question was “what do you see here?” and it encompassed everything from staging, guard equipment, the strength of marching and form awareness, and even uniform trousers. Below is a synopsis of our conversation and the methodology employed to design the show’s introduction and first hit.

SK – “OK . . . let’s look at this musically first. Looking at the score, we have a driving into in the battery percussion that is joined by the pit percussion, woodwinds, alto voices and finally brass as we come to the first hit. I know the battery is young but can they handle being the center of focus for 48 counts or so?”

MD – “It won’t be a problem. Just don’t spread them out too far. They need to hear into the middle of the section”.

SK – “Fair enough . . . what equipment is the guard planning to come off the line with?”

Guard – “Flags right now. We don’t march weapons”.

SK – “Since the opening movement is entitled “Vapor”, do you think we could come up with something softer than a flag? Maybe body?”

Guard – “Body would be good. What if we were to use large exercise balls? We could play up the water molecule angle.”

SK – “Great idea! We can introduce them in various parts of the field and bring them together as we introduce the musical voices into the first stand still”.

MD – “Remember we only have 9 girls in the guard”.

SK – “OK. How about using a soloist with a ball and the other ladies join in with the woodwinds? From there we can build to the hit. How about form? I would like to see groups in different parts of the stage. Maybe utilize some body work in the winds to reach for a higher box on the GE and marching sheets?”

Marching – “We can do that. Just make sure the movement is repetitive and not overly demanding”.

SK – “I’m thinking large gestures and poses. Nothing too crazy. This will have to play to a football crowd too”.

Obviously, there was a great was a great deal more conversation than that but it gives you the idea of the process. After this portion of our meeting, I went back to summarize and make sure we were all in agreement before I began to chart. The summarization is as follows:

- Starting Line: Battery focus with guard soloist. To create sense of formlessness the winds will support in pods utilizing movement, posing or gestures. Guard will have open stage or be placed in pods with winds.

- Guard Equipment: Exercise balls.

Each major section of the show design went through a very similar process until we had a rough outline of the over all show.

Before we begin to discuss the drill design specific to this project, we first want to establish common compositional techniques used by all drill designers. These techniques are used individually and often in conjunction with others.

- Linear – straight line patterns either in verticals, laterals or diagonals.

- Curvilinear – Curvilinear patterns are combinations of arcs (parts of circles) or curves (parts of ovals).

- Single Line Manipulation – Single Line drill puts elements into a single line that is flexed and pulled to create patterns. The Cadets are best known for using this single line drill for their trademark “whiplash” movements.

- Follow the Leader – pulling elements around an established form from a single dot.

- Arcs – Using parts of circles.

- Mass form (blob) – pulling elements into a solid form without establishing any linear connection.

- Solid Form – Pulling elements into tight vertical and lateral lines. Can be in many shapes but the most common are blocks and wedges.

- Diffused / Random staging. Similar to mass form but the spacing between elements in much greater. Also known as scatter drill, a diffused set establishes no recognizable patterns or shapes.

Basic Staging

When writing for a band, the visual elements you offer are important, but don’t forget that marching band is first a musical activity and that the sections of the ensemble should be staged in such a way as to give the most visual impact without impeding the musical presentation.

The Power Zone

The area of the field between the 35 yard lines and from the front sideline to the front hash is commonly referred to as the Power Zone. A drill designer will place his strongest voices (brass) within this space to get the most volume impact from a particular moment in the show. In many cases, the drill designer for a small ensemble will keep the entire group in this space for the duration of the show.

The Winds

- In general, try to keep like voiced instruments and similar musical parts together. This keeps the musical ensemble tighter and also presents a cleaner line for the eye to view forms.

- Staging winds for the marching band is usually the opposite of the way a concert band is set up. Unless the woodwinds are directly featured musically, I prefer them to be staged behind the brass. As they project less than the other brass instruments, I also like to keep the basses more toward the front of the ensemble when possible. This keeps the pyramid of sound more intact.

The Percussion Battery

As we all know, the drum line works as the metric pulse that holds the marching ensemble together. It is important that the staging demands placed on a drum line match well with the strength and maturity of their playing. A strong drum line that has played together for some time can handle many high level visual demands placed on them and manage to drive the show well from any where on the field. Younger, less experienced drum lines need to be handled with more care to ensure good ensemble not only with in the line but for the band as a whole. Below are a few simple suggestions to keep in mind when writing for a young drum line.

- Keep the battery together at all times. Young drum lines often rely greatly on the few strong players within the section to hold things together. Along these same lines, try to

- Establish your center and end snare drummers and keep them in the same order whenever possible. Many drum sections are set up with their strongest players in these positions to keep them set. Also, many drum lines are taught to watch or listen in to the center snare.

- Bass drum lines may be inverted but never change their order. Bass drum parts are usually written to walk up and down the section. Changing their order can cause too many ensemble problems with in the line.

- Though you need no longer write basic “elevator” drill where the drum line simply marches up and down the 50 yard line, do try to keep the battery staged between the 30s and near the back of the ensemble when ever possible. This helps lesson the chance of side to side phasing within the ensemble and also makes the wind sections feel more comfortable hearing a strong rhythmic pulse at their backs.

- If the band for which you are writing has sideline percussion, try to keep the battery forward of the back hash. Pushing the drum line too far back field can cause serious timing issues with the pit and will force the marching battery to play ahead of the beat to correct the problem.

Spacing

The space between performers dictates clarity of your form development and also musical impact. Though these can be changed with in a show, below are a few rules of thumb that I try to follow when writing.

Percussion:

- Snares – 2 Step

- Tenors – 3 Step

- Bass Drums – 4 Step

- Cymbals – 2 to 4 Step

Winds

- Tubas

- Sousaphones – 4 Step

- Over the Shoulder – 2 to 4 Step

- All Other Winds – 2 to 4 Step

Guard

- Weapons / Dancers – 4 to 8 Step

- Silks – 4 to 12 Step

Step Sizes

Although step sizes will vary form position to position, below are a few of the most common

- 8 to 5: Comfortable for all sections.

- 6 to 5: More velocity. Only slightly larger than the step size of the average person.

- 5 to 5: Larger than average step size. Should only be used for short periods and at moments that are not musically challenging.

- 4 to 5: This is a standard “jazz run” step. Use only for short periods and moments that are not musically challenging. Avoid using this step size with tubas, bass drums and tenor drums.